Youth Leadership in Haiti

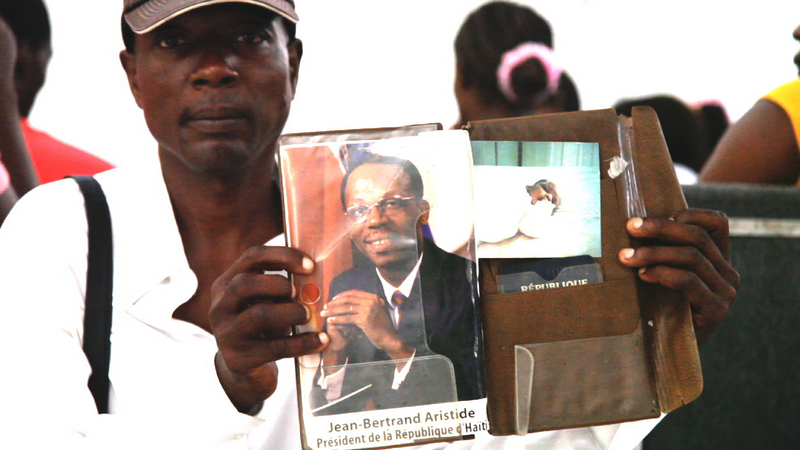

On Wednesday February 3, more than seven hundred young people gathered at the Aristide Foundation for Democracy to launch the Aristide-Lavalas Youth league (Ligue de la Jeunesse Aristido-Lavalasse). The goal of the Youth League is to bring young people together to vitalize Haiti’s democracy and to initiate service projects to help their communities in the fields of education and health.

Each department of Haiti was represented by a delegation of 10-12 young people all of whom made the long trip to Port-au-Prince because they want to contribute to the building of a participatory democracy in Haiti. Early in the morning of Feb 2, these departmental youth delegations met for a four-hour discussion/ workshop in the conference room of the AFD to share perspectives, brainstorm ideas, and create an orientation for the new organization. Pyschologist Wladimir Constant facilitated this dialogue titled, “The Leadership of the Young.”

For the second stage of the event the delegations came downstairs, and onto the stage of the auditorium, where they were welcomed with thunderous applause by over 700 other young people from the department of the West (Port-au-Prince and surrounding areas), who gathered in the auditorium to welcome the national delegates and to officially launch this Youth League.

Much of the organizing to launch the Youth League was done by young UNIFA graduates together with the leadership of the Foundation. These young doctors who began their medical training at UniFA before the 2004 coup d’etat, and then finished their training in Cuba, are now back in Haiti and have been central to all the AFD’s efforts to assist in the wake of the earthquake. This initiative also builds on the Foundation’s efforts over the past year to empower young people to be at the forefront of service in wake of the quake (though mobile clinics staffed by young doctors, mobile schools staffed by young high school and college graduates, and our youth-led mental health project Soulaje Lespri Moun, and the the reopening of UNIFA ).

The launching of this youth league represents the determination of all the young people who have came together on February 3, to offer their energy, creativity, and vitality towards a new Haiti.

Rose Yvica Roche Volcy and Yves Merry Stuart Roche were the MC’s for the ceremony in the auditorium. Hancy Pierre Louis, professor of economics and former Vice Governor of the Central Bank, gave a presentation on Haiti’s economy.

Wladimir Constant, spoke again on the centrality of youth leadership, and Toussaint Hilaire, the Director of the Arsitide Foundation spoke about the importance of youth gaining confidence in themselves through service to the country and offered perspectives on the kinds of civic and service projects the Youth League might undertake, such as literacy programs for adults, and educational projects for children who are not in school.

Joseph Marc Anderson, a youth representative then spoke on behalf of the league and presented its charter to those present.

A cultural presentation by Kolonb Dor, the youth troupe of the Aristide Foundation followed.

We look forward to seeing this new organization evolve and flourish. Only Haitians can rebuild Haiti.

In Haiti, Reliving Duvalier, Waiting for Aristide

Published on the Huffington Post January 24, 2011, Commentary by AFD board menber, Laura Flynn

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/laura-flynn/not-even-the-past_b_813172.html

In Haiti, Reliving Duvalier, Waiting for Aristide

January 25, 2011

In the 1980s, when the armed forces of Jean-Claude Duvalier’s regime set about exterminating “Haiti’s Creole pigs”, they would come to Haiti’s rural villages, seize all of the “pigs”, pile them up, one on top of the other, in large pits and set fire to them, burning them alive.

A Haitian friend recounted this story to me this week. It was an image that she could not get out of her head since Jean-Claude Duvalier returned to Haiti. Because that’s what it was like for her, to watch Duvalier be greeted like a dignitary at the Port-au-Prince airport, and then escorted to his hotel by UN military forces — like being burned alive.

In 1968, when my friend was 3 years old, members of Duvalier’s Tonton Macoutes came to her home at 3 o’clock in the afternoon as her extended family shared a meal in the courtyard of their house in the Port-au-Prince neighborhood of Martissant. The Macoutes dragged her father and two of her uncles away. They then went to two other houses on her block, and took away all the men from those families as well. Her father and the other men in the neighborhood were members of MOP, the mass political party of Haitian populist leader Daniel Fignolé, which Duvalier wiped out, along with all other forces of opposition in the country.

None of the men taken from Martissant that day were ever seen again. They disappeared, perhaps perishing in the Duvaliers’ infamous prison, Fort Dimanche, after enduring torture, beatings, and starvation. The families could not even hold public funerals, and they never recovered the bodies of their loved ones. With the help of a sympathetic nun, my friend’s mother did manage a clandestine a mass for her husband, and later she consecrated an unmarked, empty tomb for him in Haiti’s National Cemetery. To this day, she visits that empty tomb on All Spirits Day each year to honor the husband she lost over 40 years ago.

The common wisdom, repeated endlessly in the international press since Duvalier’s return, is that Baby Doc’s regime was less repressive than his father’s. But my friend’s mother does not remember it that way. Left to raise six children on her own, she lived for nearly 20 years –until the fall of Baby Doc in 1986 — in constant terror that she or her children would be targeted again. Each day, the children rushed straight home from school and didn’t leave the house again. Each summer as soon as school ended, she packed them off to the countryside to breathe a sigh of relief.

Under Baby Doc the most spectacular violence, the murdering of whole families, mass purges of the military, and especially violence targeting Haiti’s wealthy families, abated. But the intimate terror the Duvalier regime exercised over every aspect of daily life continued. In Martissant, as in most Port-au-Prince neighborhoods, there were active members of the Macoutes in every other home. With almost unlimited power, they spied on and policed their neighbors, attacking, arresting, even killing people for such infractions as wearing an Afro, not wearing shoes, or leaving a light on after dark. Since the Macoutes were not formally paid, and since the economy was in a free fall, they enacted daily violence and extortion on the population to survive.

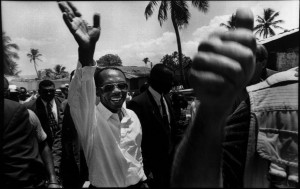

The children of those taken in Martissant that day in 1968 never forgot what happened to their fathers. As soon as they were old enough — just kids really, 12, 13 years old — they found themselves drawn into, and then propelling forward, a movement for change. Each Sunday morning, a chain of young people from Martissant set off across the city, jen pase pran jen, young people gathering more young people, until they numbered in the hundreds, arriving at doors of St. Jean Bosco in La Saline where a young priest was saying out loud what they had been saying in their hearts all their lives: Fok sa Chanje. This must change. These young people, joined by thousands of others in church and grassroots organizations across the country, ignited a movement that after long struggle and many lost lives, finally overthrew a 30-year dictatorship.

Market Women – the Heart of the Nation

Marie José Paul, a recipient of a loan from the Aristide Foundation, in front of her business.

This past August sixty market women gathered at the Aristide Foundation for Democracy to plan and discuss the opening of a micro-lending initiative. The earthquake had a devastating impact on the small businesses of the woman gathered. Many had lost homes, businesses and/or inventory. Almost all were living in tents or other temporary housing and lacked the funds to restart any commerce to support their families.

Since its inception in 1996 the Foundation has worked closely with women in the informal sector, making loans, selling food at low prices, and helping them to build organizations to advocate on their behalf. This summer with assistance from Haiti Emergency Relief Fund the AFD launched a women’s micro-lending project with a small loan fund of $7,000. A first group of 20 women received further training in early September, after which loans were made on September 8, 2010. Each woman received a loan of 12,000 gourdes ($300US). Interest on the loans is 5% (bank interest rates are 20%-30%). The loans are for a five-month period, with early repayment allowing them to pay less interest. The project is directed by Gladys Delouis, a long-time organizer with the AFD, and overseen by Director Toussaint Hilaire.

The 20 women who received loans sell their goods at the markets of Croix-des-Bouquets, Croix-de-Missions, Croix Brossals (the main market in downtown Port-au-Prince), Tabarre and Cite Soleil. The small businesses they launched with the loans include: selling cooked food by the plate (manje kuit), selling raw food (manje kri), fried snacks (mange fritay) as well as selling charcoal (marchand charbon) and clothing (marchand vetman). A couple of the women in the group, who live in La Plaine and have access to land, borrowed money to plant quick growing food stuffs which they plan to harvest and sell. Of the 20 women who received loans, 17 are the sole providers for their families.

The markets where these women sell their goods are the commercial hubs of their communities. In these markets, and many others across Haiti, thousands and thousands of men and women work, and many more thousands of Haitians buy their daily necessities. Historically, the markets that serve Haiti’s poor majority were ad-hoc, unplanned, and dirty. While Aristide was President from 2000-2004 fifty-three public market places across the country were constructed or repaired—including all of the markets listed above, where the women in this project work. Clean and dignified stalls were created for vendors, roofs, drainage, and toilets were put in. Public literacy centers, and medical clinics were set up inside the markets for the benefit of both sellers and customers. Since the coup in 2004, most of these facilities have fallen into disrepair because the state does not bother to maintain them. Programs like the marketplace literacy centers and health centers were abruptly abandoned—facts well know in on the ground in Haiti, if virtually ignored internationally.

Since September, the 20 women in the micro-lending project have been meeting at the Foundation every 15 days, to check in, share ideas and continue to shape the program.