The exceptional resilience demonstrated by the Haitian people during and after the deadly earthquake reflects the intelligence and determination of parents, especially mothers, to keep their children alive and to give them a better future, and the eagerness of youth to learn – all this despite economic challenges, social barriers, political crisis, and psychological trauma. Even though their basic needs have increased exponentially, their readiness to learn is manifest. This natural thirst for education is the foundation for a successful learning process: what is freely learned is best learned.

Of course, learning is strengthened and solidified when it occurs in a safe, secure and normal environment. Hence our responsibility to promote social cohesion, democratic growth, sustainable development, self-determination; in short, the goals set forth for this new millennium. All of which represent steps towards a return to a better environment.

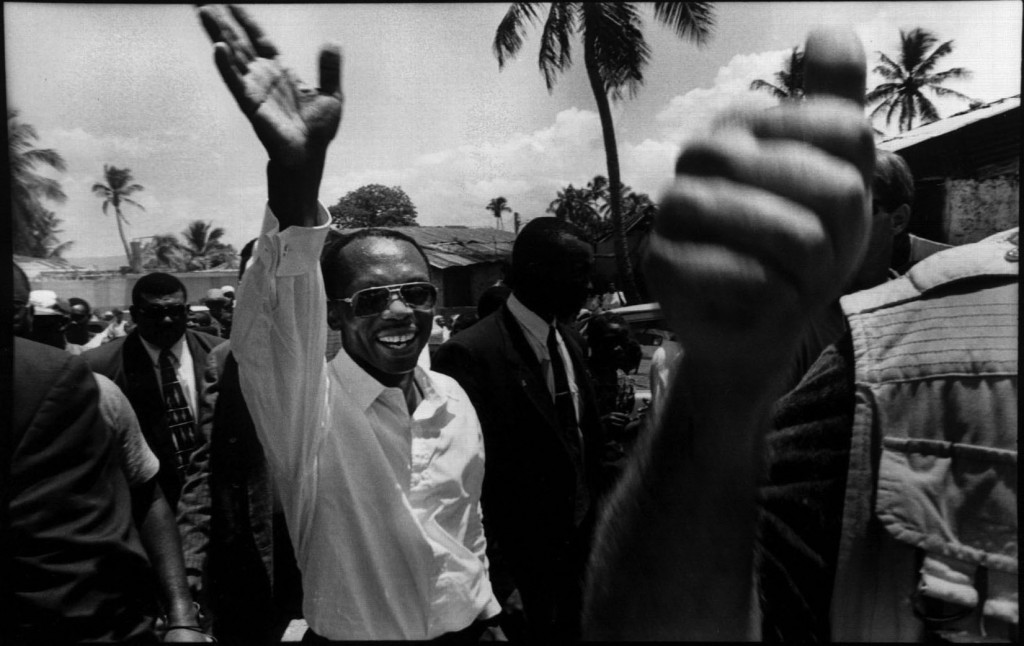

Education has been a top priority since the first Lavalas government – of which I was president – was sworn into officeunder Haiti’s amended democratic constitution on 7 February 1991 (and removed a few months later). More schools were built in the 10 years between 1994, when democracy was restored, and 2004 – when Haiti’s democracy was once again violated – than between 1804 to 1994: one hundred and ninety-five new primary schools and 104 new public high schools constructed and/or refurbished.

The 12 January earthquake largely spared the Foundation for Democracy I founded in 1996. Immediately following the quake, thousands accustomed to finding a democratic space to meet, debate and receive services, came seeking shelter and help. Haitian doctors who began their training at the foundation’s medical school rallied to organised clinics at the foundation and at tent camps across the capital. They continue to contribute tirelessly to the treatment of fellow Haitians who have been infected by cholera. Their presence is a pledge to reverse the dire ratio of one doctor for every 11,000 Haitians.

Youths, who through the years have participated in the foundation’s multiple literacy programmes, volunteered to operate mobile schools in these same tent camps. In partnership with a group from the University of Michigan in the US, post-traumatic counselling sessions were organised and university students trained to help themselves and to help fellow Haitians begin the long journey to healing. A year on, young people and students look to the foundation’s university to return to its educational vocation and help fill the gaping national hole left on the day the earth shook in Haiti.

Will the deepening destabilising political crisis in Haiti prevent students achieving academic success? I suppose most students, educators and parents are exhausted by the complexity of such a dramatic and painful crisis. But I am certain nothing can extinguish their collective thirst for education.

The renowned American poet and essayist, Ralph Waldo Emerson, wrote that “we learn geology the morning after the earthquake”. What we have learned in one long year of mourning after Haiti’s earthquake is that an exogenous plan of reconstruction – one that is profit-driven, exclusionary, conceived of and implemented by non-Haitians – cannot reconstruct Haiti. It is the solemn obligation of all Haitians to join in the reconstruction and to have a voice in the direction of the nation.

As I have not ceased to say since 29 February 2004, from exile in Central Africa, Jamaica and now South Africa, I will return to Haiti to the field I know best and love: education. We can only agree with the words of the great Nelson Mandela, that indeed education is a powerful weapon for changing the world.

(this piece was originally published in the Guardian on February 4, 2011, you can see the original here)